The Political Compass – More than Just a Meme

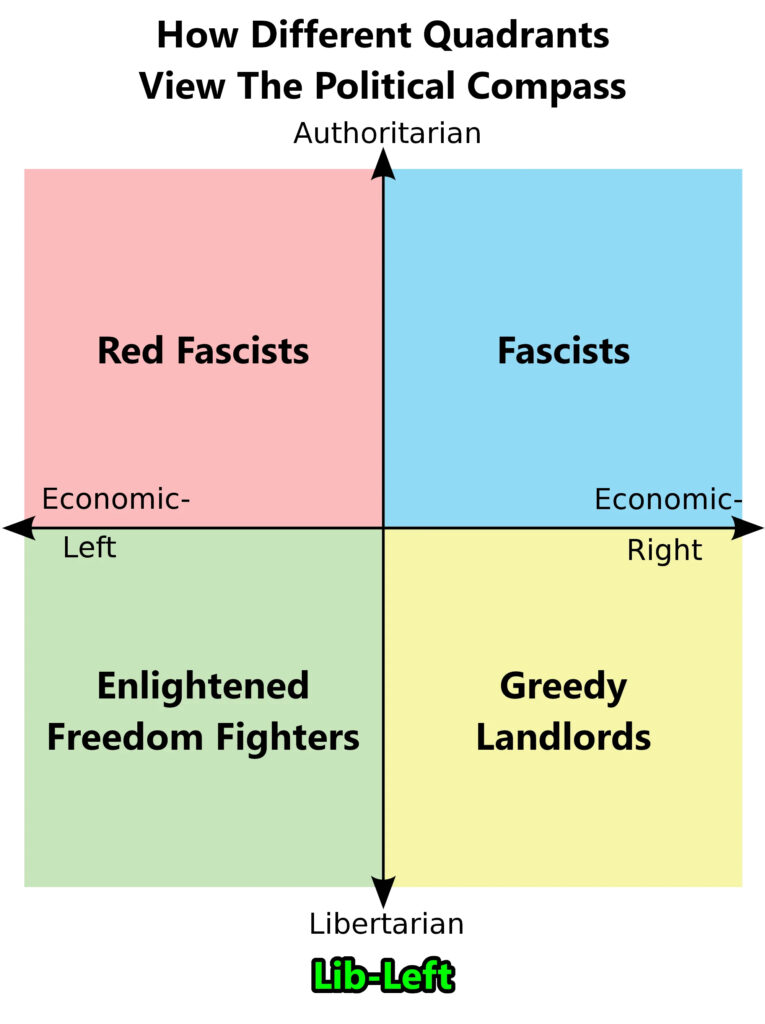

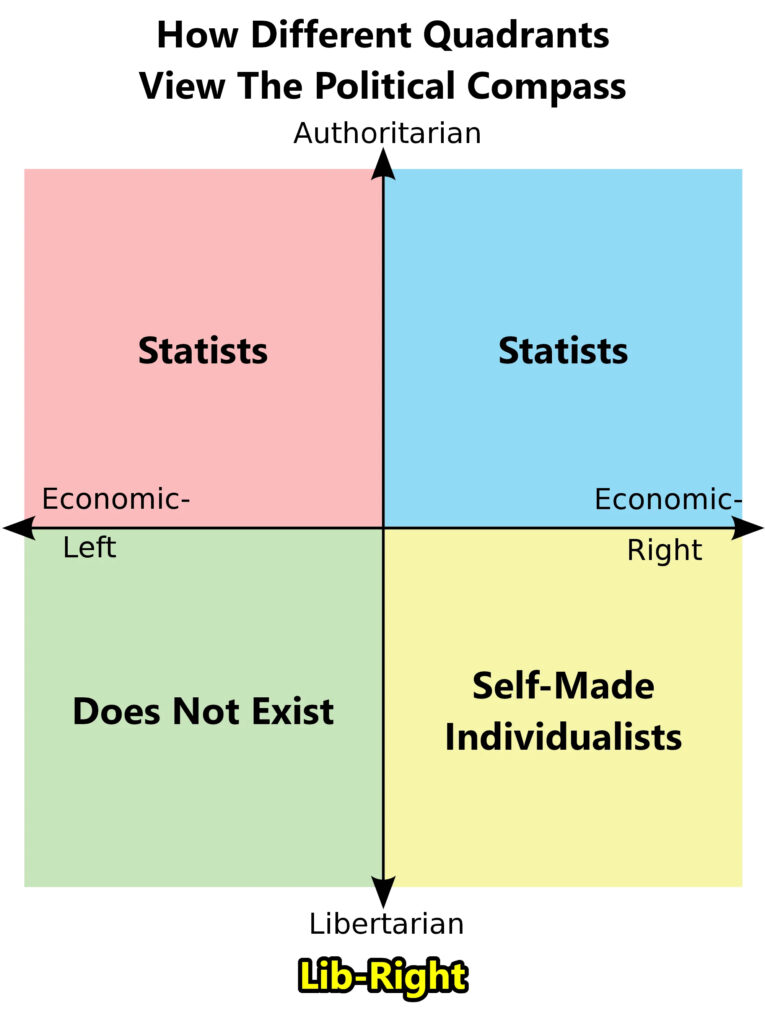

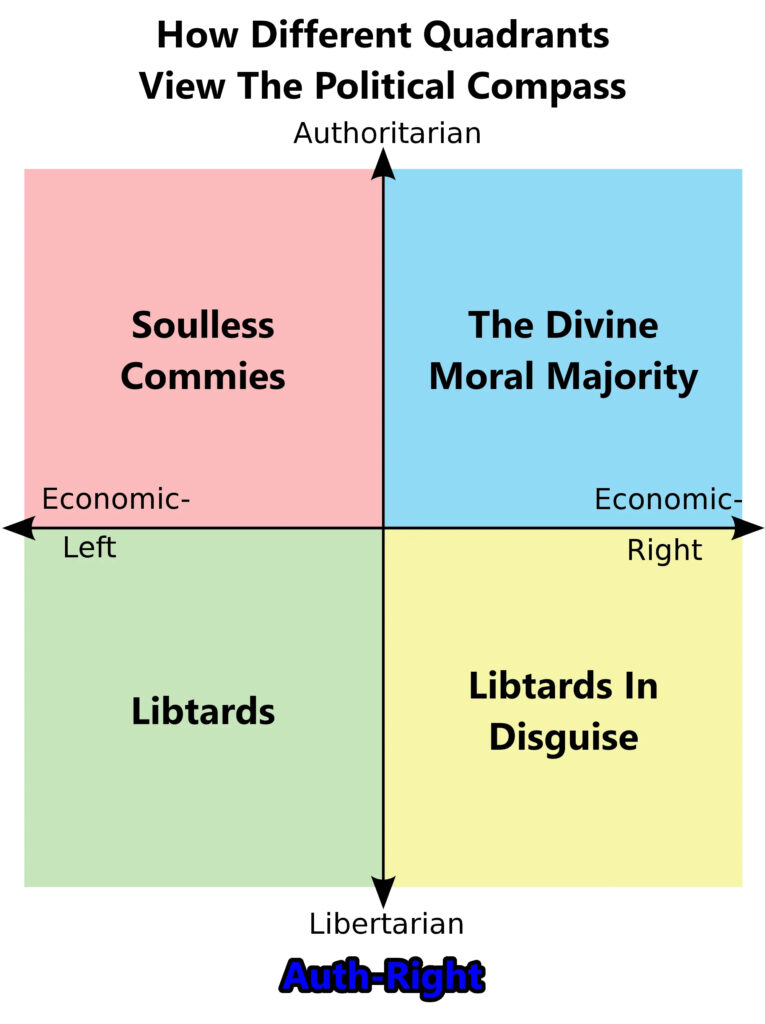

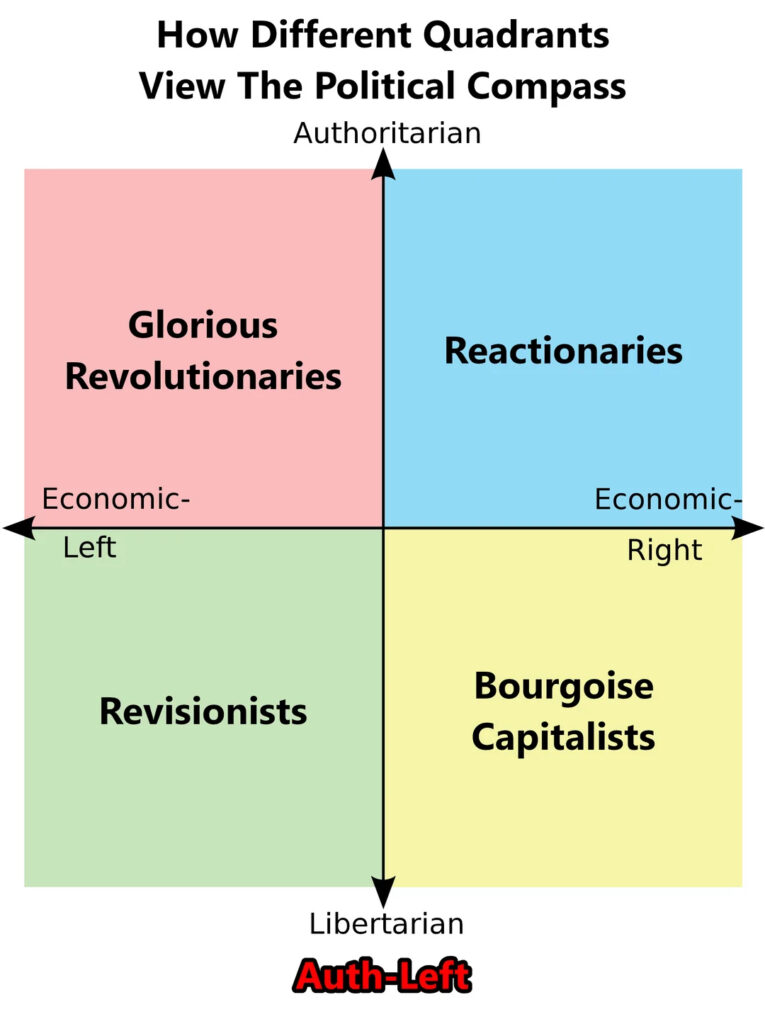

Despite its designers’ hopes that it might beckon in a new era of more nuanced political discourse, the political compass has largely been reduced to meme-fodder:

This popularised version of the political compass has now been around for over 20 years, and by that metric, this post is a bit late to the party, however the concept of expressing political alignment using 2 dimensions is far older than this.

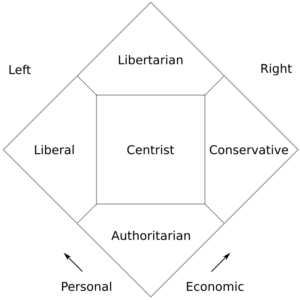

The American libertarian David Nolan came up with his “Nolan Chart” way back in 1969. It is very US-centric, and was created specifically with the goal of converting people to libertarianism, however I can’t help but feel that despite this, it is just more elegant than the political compass.

The more popular incarnation, that is the subject of so many political memes, has plenty of its own limitations and biases, but it also completely fails to be memorable (“Authoritarian-Left” doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue). Thankfully John Nerst at EverythingStudies wrote a pair of posts back in 2019 that reformulate the whole idea, addressing many of the limitations, and it is his “tilted political compass” that I want to build on. If you haven’t read those two posts, and are interested in the subject of political alignment, I strongly recommend that you do so right now. This post will still be here when you get back!

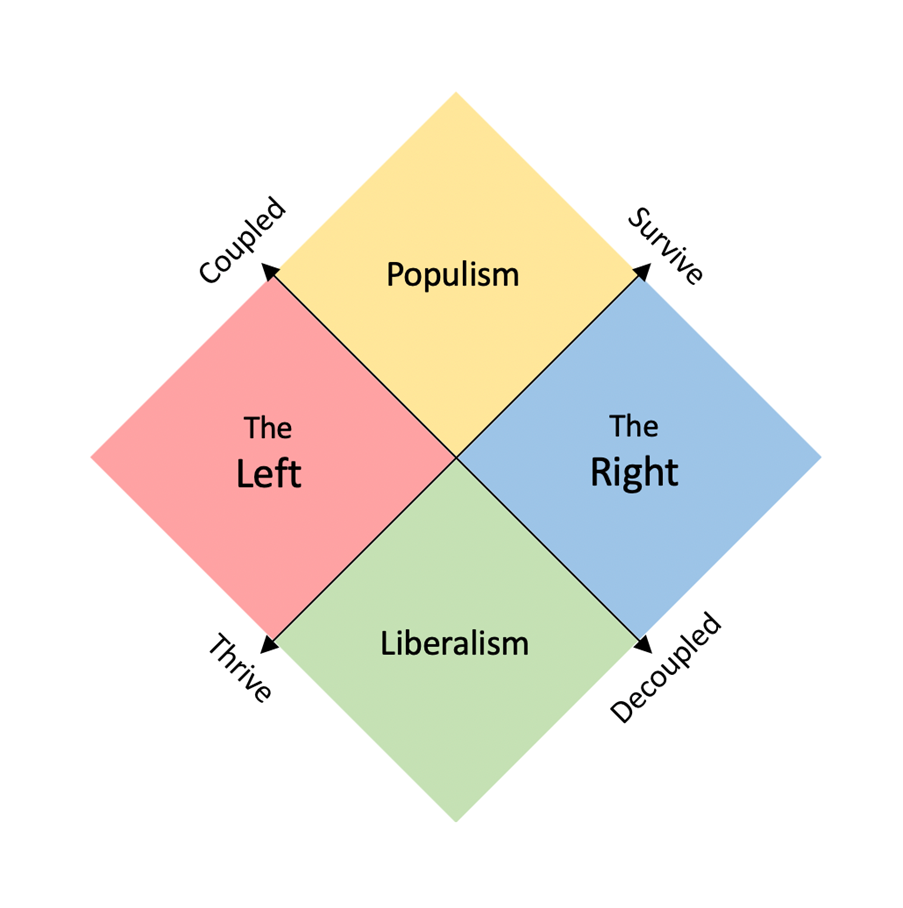

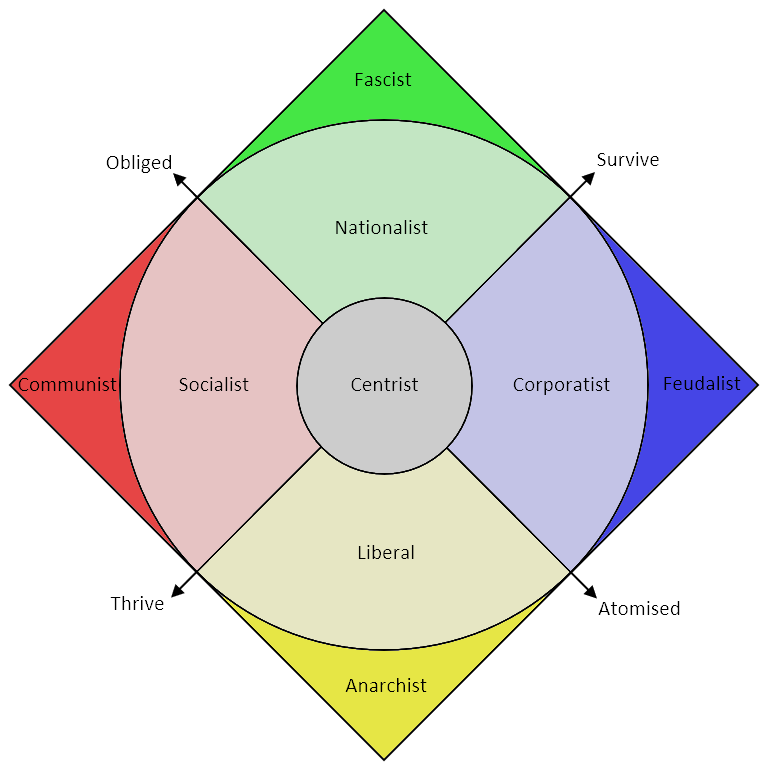

As a very brief summary, he proposes changing the axes from “Left-Right” and “Authoritarian-Libertarian” to “Thrive-Survive” and “Coupled-Decoupled”, in such a way that these new axes cut diagonally across the old ones, as follows:

In decoupled society the default relationship between two people is that of no obligations whatsoever… The only obligations are to respect explicitly stated rights and agreements. No expectations beyond that are valid.

In coupled society what it means to be a good person or what may be required of you at any point is open-ended. There are not clear boundaries between people and you are expected to take others’ or society’s interests into account as much as your own.

In a “survive” scenario (think famine, war or zombie apocalypse) mistakes are costly, outsiders are potential threats, keeping order is paramount and we can’t afford to be too generous towards the weak lest they pull us down with them.

In a “thrive” scenario by contrast (think true post-scarcity in a future automated economy), where we don’t even need to think about making a collective living we can afford almost limitless generosity towards the “other”.

When I first read these two posts, I loved them immediately. The change to using an axis of “Thrive-Survive”, inspired by a SlateStarCodex post, readily conjures up worldviews and behaviours that align quite well with the politics it aims to describe. The second axis of “Coupled-Decoupled” is a very useful concept that rather neatly expands the spectrum into a plane that maps very well onto the original political compass, whilst providing more insight and being more descriptive.

Looking at Nerst’s compass alongside Nolan’s chart, you could be forgiven for thinking that he has reinvented the wheel, but I would argue that Nerst’s compass is much deeper, more general, and less US-centric. At first glance, “Thrive-Survive” feels a bit like “Economic Freedom”, and “Coupled-Decoupled” feels a bit like “Personal Freedom”. However, whilst the “Freedom” axes seem to work pretty well (people on the right generally like lower taxes, which counts as economic freedom, and people on the left generally like bodily autonomy which counts as personal freedom), they aren’t able to explain some correlations between political views quite as effectively.

For example, if the right is defined by being pro- economic freedom, you might expect right-wing people to be in favour of immigration, as this allows people access to cheaper labour. Generally speaking though, the right is often more concerned with reducing immigration than the left. This is very easily explained however by the right being defined by a Survive perspective instead.

Similarly, if the left is defined by being pro- personal freedom, you might expect left-wing people to be very in favour of free speech. Again however, the left is often more willing to compromise on free speech to achieve other aims. The Nolan Chart’s “left” is labelled “Liberal”, which shows its US-centricity – Socialism was such an anathema in 1970s America, that there was no need to fit it into the chart! Personal freedom is much less of a core value for Socialists than it is for Liberals. As such, if we want to include the whole gamut of left wing ideology within the compass, we have to use a different measure for our axis.

John Nerst also demonstrates that this formulation does an excellent job of explaining why the left-right axis in Europe behaves so differently to the left-right axis in the US. This framing of political alignment gave me plenty to think about, and I’ve wanted to write down these thoughts for some time.

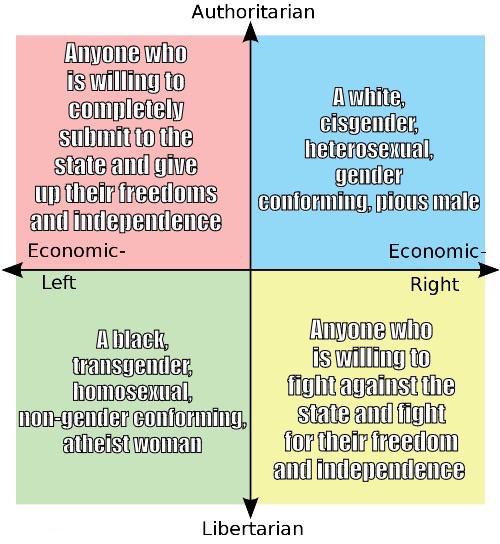

“The Ideal Human (according to each quadrant)”

I was intrigued to find that Nate Silver recently wrote an article in which he basically rediscovered something like this “tilted political compass” framing of politics, just missing the top quadrant. This suggests that despite being several years old at this point, the ideas in the EverythingStudies posts are still both useful and heterodox. I hope therefore, that post is just as relevant to the present political situation as when Nolan first conceived his chart 55 years ago.

The Axes

The Thrive-Survive axis is perfect – as mentioned above, it needs very little explanation. Sadly, the Coupled-Decoupled axis is rather more subtle – they are not the most descriptive words, requiring explanation before their meaning becomes clear. What is more, Coupled and Decoupled were originally used in a cognitive sense, rather than a political one, meaning that further disambiguation is required.

As such, I would be strongly inclined to use some other words that more readily conjure up the concepts that are being described. The words that I have come up with for either end of this axis, that I think are the most immediately expressive of the concepts being alluded to, are to describe individuals within a society as being either Atomised from each other, or Obliged to each other. Replacing Coupled-Decoupled with Obliged-Atomised makes no fundamental change to the model, but reduces the need to preface the model with an explanation about what is being meant by societal coupling. Going forwards I shall use this language.

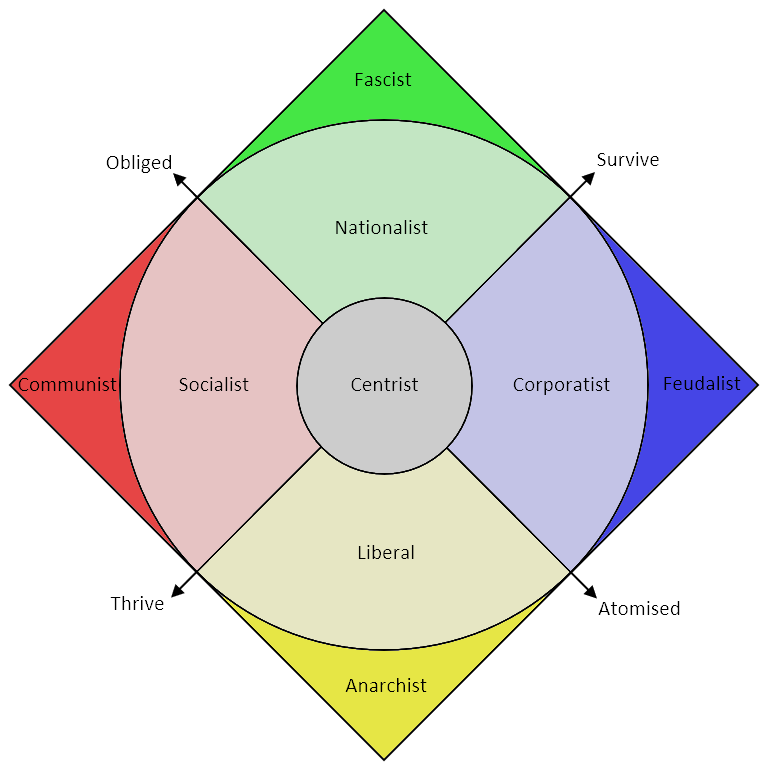

Bottom Quadrant

Like John Nerst himself, “Atomised-Thrive” is the quadrant that feels like home to me. Classical Liberalism describes this quadrant very well, and J.S. Mill’s “On Liberty” provides an excellent reference point. Of course, in the US, the label Liberal has rather unhelpfully taken on a more left wing connotation, but the EverythingStudies posts have already dealt with this at length.

It has been suggested that Libertarianism is the extreme of Liberalism, but I disagree with this assessment – Libertarianism is neither sufficiently extreme nor sufficiently Liberal to qualify. Whilst strongly prioritising personal freedoms and a very Atomised society, current Libertarian movements are not very focused on “Thrive” concepts such as encouraging human flourishing, preferring instead to prioritise property rights as a panacea. Equally though, they do not appear to be focused on “Survive” either, as a fairly critical presumption of Libertarianism is that; even with a very bare-bones government, everything will basically be fine. This puts Libertarianism towards the edge, in between the bottom and right quadrants.

For the extreme of the bottom quadrant, the only label that makes sense to me is Anarchism. This extreme represents an absolute atomisation of society, resulting in a complete absence of formal structures, combined with a confidence that we live in sufficiently bounteous times that humanity will not immediately start tearing itself apart. Although Anarchism is perhaps perceived as less worrying than a column of marching Fascists, due to its inherent disorder; it would still be dangerous to view this kind of extremism as entirely benign. I personally am not convinced that we are living in a sufficiently bounteous era, and therefore I would argue that by its very nature, Anarchism implies the death of civilisation itself.

Top Quadrant

The label of Populism for the top quadrant doesn’t quite work for me, because the particular thing that happens to rile people up at any given time can vary significantly (EverythingStudies does mention that this isn’t an ideal label). A populist is a politician that shamelessly adopts whatever policies are being pushed by those that are shouting the loudest at the time; regardless of whether they think that they are wise, simply to improve their chances of being elected. I don’t think that Singapore is particularly populist, but I would consider it to be a very good modern example of an Obliged-Survive society. The heavy-handedness of the Singaporean government (for example, outlawing chewing gum, heavily restricting immigration or requiring an exceedingly expensive permit to own a car) ultimately enforce a kind of cultural unity, and facilitate an orderly and efficient society.

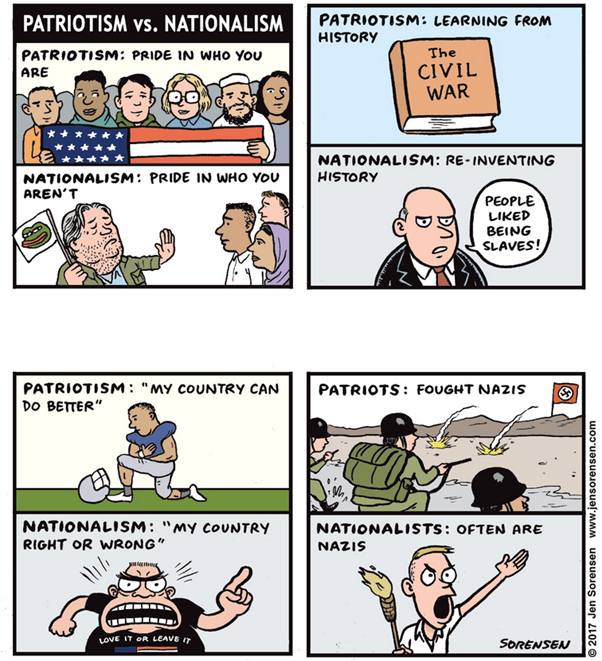

I prefer to label this quadrant Nationalism, as this feels very descriptive of the Obliged-Survive approach to society. A Nationalist country behaves a bit like a family unit – everyone has obligations to it (and therefore to each other), and in exchange the country has a duty to protect all of its citizens and its culture from threats domestic and external. As EverythingStudies notes, the mid-20th Century issues with Fascism, which is the extreme of this quadrant, made this whole quadrant feel toxic. The label of Nationalism is similarly contaminated by this association, and is sometimes used as a pejorative:

This comic is a good example of this conflation. I don’t like the idea of using patriotism to describe the top quadrant, as this would suggest that people in the other quadrants can’t be patriotic.

Whilst Nationalism doesn’t align with my personal politics, I think it is very harmful for it to be considered universally bad, as such judgments tend to drive people more towards the extremes. There is nothing uniquely bad about the combination of “Obliged-Survive”, it is just another perspective on the world that has some benefits and some drawbacks. The furthest reaches of this quadrant may be most accurately called Fascism, but name calling only serves to shut down discussion. After all, every quadrant has its extreme point, and if we were to conflate the extremes with the entire quadrant, that would be the death of any attempt at civilised conversation.

Singapore is a perfectly reasonable society, and whilst I would personally prefer to live in a more free and liberal country, plenty of people like it, and it is very successful. Treating Nationalism as just another viable option, leaves more room for people to come together and compromise.

Left & Right Quadrants

The left and right quadrants could really do with some more descriptive names. Socialism works for the left, “Obliged-Thrive” quadrant – it is a generic enough ideology, with many possible qualifiers – democratic socialism, liberal socialism, nordic socialism, etc. These are all variants that cover different implementations of an overarching philosophy. At its extreme, Communism is a fairly descriptive label, which much like Fascism, evokes shudders from a good proportion of the public.

How then can we describe the right? Conservatism doesn’t really work, as this is not really precise enough – conservatism can mean traditionalism, which is very much aligned with the survive end of the Thrive-Survive axis, but is not specifically “atomised” (traditionalist central planners exist, and definitely don’t fit in this quadrant). Conservatism can also be used to describe a position of favouring the status-quo, or making small incremental changes as opposed to radical shifts. It is only through the branding of certain political parties that it has come to be synonymous with the right in certain geographies. Capitalism doesn’t really work either – despite free markets and capitalism being quite aligned with the “atomised” end of the Obliged-Atomised axis, it doesn’t really have an affiliation to either survive or thrive. Traditionalist capitalists absolutely are in the right hand quadrant, but progressive capitalists are in the bottom one.

The term “Neo-Liberal” could be used to describe this quadrant, but I personally hate this term: it is confusing (we have already used the term “Liberal” once), and it is not at all descriptive, requiring a history lesson to properly understand what “Neo” represents, and why it is fundamentally different to classical Liberalism. I am instead inclined to use the word Corporatism to describe this quadrant. Below is a quote lifted from the Wikipedia article:

Corporatism is a political system of interest representation and policymaking whereby corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, come together on and negotiate contracts or policy on the basis of their common interests. The term is derived from the Latin corpus, or “body”.

Corporatism does not refer to a political system dominated by large business interests, even though the latter are commonly referred to as “corporations” in modern American vernacular and legal parlance; instead, the correct term for this theoretical system would be corporatocracy.

Importantly, this is quite a broad term, which fits well with having to describe a whole quadrant. Similar to the other quadrant labels, there are a variety of different ways to implement Corporatism, some of which have overlap with the other quadrants. The general principle encapsulates a kind of contract based, dog-eat-dog worldview that seems likely to arise from an “Atomised-Survive” society. Corporatism also treats these non-governmental entities as the primary agents and stakeholders in any kind of action or negotiation, which appears to align well with political parties in this quadrant, who prefer such things as privatisation and industry self-regulation over state control.

The extreme of this quadrant is an interesting one, as I don’t believe that it currently has a consistent or recognisable name. “Far-right” is most often used to describe Fascism, which sits in the top extremity, rather than the right-hand one. “Anarcho-Capitalist” is also a possibility, and is often used to describe extreme Libertarianism, but like Libertarianism itself, this doesn’t really fully encapsulate the Survive perspective. It is also too similar a word to Anarchism, which we have already used for the bottom extremity.

Corporatocracy is explicitly mentioned in the above quotation, as meaning something different to Corporatism, but helpfully a Corporatocracy is a kind of government you are likely to get when Corporatism is taken to extremes. Specifically, it is what Corporatism becomes when the corporations become too powerful and start to either dominate or replace the government. Given the already existing confusion about these two similar sounding concepts however, this is not the best label either.

Where would we end up though, if we took the already extreme situation of Corporatocracy, and pushed it even further? Companies are already much like governments, insofar as they have enormous power over their employees for 8 hours a day, 5 days a week, and whilst they might pay taxes to a higher power, the more autonomy they have within the system, the more they appear like a state in their own right. In this Corporatocratic dystopia, we would end up with a large number of almost serf-like employees, working for a small number of very wealthy executives, able to lord their power over the masses. I have effectively just described the feudal system, with vassal lords commanding serfs, and paying homage to a distant and comparatively weak ultimate ruler. Thus, I am inclined to call the extreme of this quadrant Feudalism – it may conjure images of medieval peasants, but the fundamental structure is very similar.

Taking the four quadrants as described above, I asked Dall-E to give me D&D style characters that represent each position. Here are the ones that I liked the best:

The Centre

The centre hides a lot of conflict – you could land in the centre by being indifferent to most questions, but equally, you could land there by feeling very strongly about many questions in such a way that they average out to a centrist position. In this way, it is possible to have two centrists that disagree about almost everything. For example, on the Thrive-Survive axis, someone could be simultaneously very strongly pro-police (Survive), whilst also being strongly pro-immigration (Thrive). This would not be a completely unreasonable position to hold, but I think it may be quite unusual.

The axes of Thrive-Survive and Obliged-Atomised have been settled upon precisely because they seem to cut through the space of political opinions in a sufficiently coherent way that such combinations of views remain quite rare. Nevertheless, it is only a model, and it is possible that some future seismic political event could result in a shift in views that renders it obsolete.

My take on the political compass therefore looks like this:

Extending the Model

No model is complete without an attempt to make it cover far more ground that was initially intended. EverythingStudies has already come up with a number of variations on the axes and quadrants that map remarkably well onto the diagram, so instead of doing more of the same, I propose some other dimensions that are not yet captured by the existing two dimensional model.

The first of these dimensions comes from yet another EverythingStudies post, in which John Nerst describes himself as Liberal, Progressive and Conservative. By this, he is meaning: Liberal as described by the bottom quadrant; Progressive in the sense that he seeks to improve things, as opposed to a Traditionalist who seeks to keep things the same; and Conservative in the sense that he seeks gradual or incremental change rather than radical change or revolution.

I think that an axis of Progressive vs. Traditionalist maps fairly well onto the Thrive-Survive axis. Whilst any such mapping is not perfect, there is an implication within the idea of Thrive, that there is enough slack in the system that improvements can be achieved. Of course, the exact direction in which progress is being sought will depend heavily on other considerations, and they might not align with how people in the US colloquially use the term “progressive”. Similarly, there is an implication within the idea of Survive, that things that have already been proven are safer, and that untested approaches risk leading us to disaster. This is probably why both Liberals and Socialists are often associated with Progressivism, whilst Nationalists and Corporatists are often associated with Traditionalism. In the future it is possible that these concepts will diverge, and we will see a large number of Progressive Nationalists, or Traditionalist Socialists, rather than these being very fringe ideas, but until then it seems like a bit of a waste of an axis.

This leaves the idea of an axis of Gradual vs. Radical, which I would argue is not well captured at all by the existing two axes. Of course, you could argue that I have just made the assertion that Traditionalists are resistant to change, while Progressives embrace it, therefore this is also covered by the Thrive-Survive axis, but I do not believe this is the case. This axis refers to the speed of change, rather than its direction.

There exist Radical Traditionalists that want to see society immediately revert back to a previous state, and there exist Gradual Progressives (like John Nerst) that want to see any potential improvement be made steadily and incrementally, to allow society to mitigate any unforeseen consequences.

This Gradual-Radical axis is quite well aligned with another conceptual spectrum – the divide between ideology and empiricism. People that subscribe to an ideology, and see the world through a particular lens, are likely to want to immediately address any issues they perceive. In contrast, those that are less ideological, and prefer to see empirical evidence before proceeding are much more likely to support an incremental approach. Philip Tetlock’s Hedgehog and Fox refer to a similar idea – the ideological “hedgehog”, making bold claims and advocating bold solutions, and the empirical “fox”, equivocating between different conflicting theories, and demanding a proven result before committing to further movement.

Into the fourth dimension

The second of these additional dimensions is another idea that at least initially appears very similar to Thrive-Survive. When we think of the Thrive-Survive axis, at least as it has been used by SlateStarCodex and EverythingStudies, it is largely an inwards looking concept. Whether the society itself is abundant with plenty or struggling to cope, providing individuals with opportunities, or protecting them from threats. What happens if instead of looking inwards at the society that our politics is governing, we instead look outwards at the wider world?

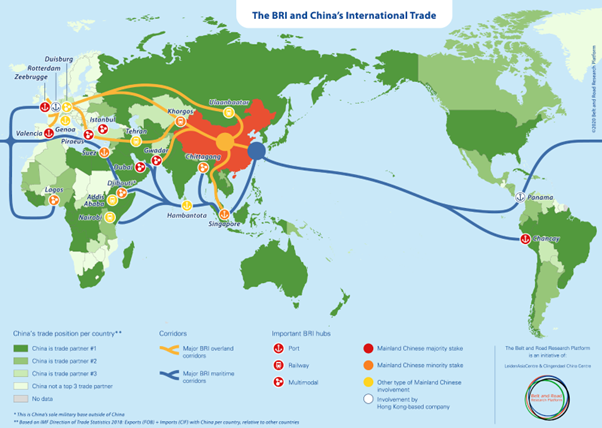

When we look outwards, we can either choose to keep ourselves to ourselves, studiously maintaining neutrality, or we can intervene, aligning ourselves with other societies and against others. There is already an established naming convention for this – Doves vs. Hawks, though to keep it consistent with the other axes, I will go with the more descriptive but less poetic Neutral vs. Interventionist.

These labels do seem to suggest that this axis is predominantly military in nature, but Intervention doesn’t have to be explicitly military. Take China’s Belt and Road initiative – this is one of the most sweepingly interventionist pieces of foreign policy that has been pursued since the cold war ended. At least on the face of it, the BRI is purely economic – a huge injection of over $1 trillion of debt into a selection of key infrastructure projects in Africa and Central Asia. Of course, there is no free lunch here – the end result of this investment is considered by many to be debt-trap diplomacy which is just yet another technique that countries can use to gain influence over one another. The BRI does have a military angle as well, but this is only one of several strategic objectives that China is pursuing, including increasing soft power, diversifying trade networks and opening new markets for export.

I think that this dimension is critically important to understanding how and why people’s voting patterns and political preferences can shift very rapidly under certain conditions. When foreign policy is not high on people’s agendas, some people may be very well aligned with a particular political party, even if they don’t necessarily see eye-to-eye on some specific policies such as military funding or international relations. When the global environment becomes sufficiently turbulent however, all of these other points of agreement can become secondary to the pursuit of their desired geopolitical outcome. Suddenly people can become willing to hold their nose and vote for someone they broadly disagree with, just because they agree with a particular foreign policy approach. If we combine this Neutral-Interventionist axis with the Thrive-Survive axis, we can provide some very informative examples of each pairing.

Warning – extreme simplification of complex geopolitics incoming:

Neutral-Survive – Switzerland is committed to neutrality, but at the same time they have a very strong military and have laws mandating nuclear shelters in many buildings.

Neutral-Thrive – Costa Rica has entirely disbanded their military, preferring to invest more in education and health instead. Although they are closely aligned with the US in some senses, because they would rely on the US military in the event of an attack; they still strive to remain largely unaligned to avoid giving anyone a reason to attack them.

Interventionist-Thrive – NATO, whilst a defensive alliance, has many members that have historically been quite comfortable with “exporting democracy”, and most European countries along with the US Democratic Party are fairly Liberal, giving NATO a relatively “Thrive” perspective.

Interventionist-Survive – Iran and Russia are also highly interventionist (Iran through their funding of Houthi rebels, Hezbollah and Hamas, and Russia through their invasions of their neighbours), whilst being firmly Nationalist, and framing these interventions as necessary for their country’s survival.

Visualising the 4 axes

Feel free to skip this section if you just want me to get to the point.

The additional axes make it no longer possible to express one’s position on a simple 2×2 grid. The first thing that came to my mind when thinking about four axes was the Myers-Briggs personality type model. This approach to personality classification is often criticised, but DynoMight has mustered a very good defence of it here. DynoMight’s adjustments to the basic MBTI model are very relevant to the discussion of political alignment too, so if we adopted this style of presentation, a similar approach of capital letters for strong views, lower case for weaker views, and x for centrism would be appropriate.

These four axes are then:

| O | o | x | a | A |

| T | t | x | s | S |

| N | n | x | i | I |

| G | g | x | r | R |

So someone mildly Interventionist, but strongly Radical and Socialist would be an “OTiR”, and someone strongly Libertarian, Gradual and Neutral would be an “AxNG”. This would make me an “atig”, as someone that is Atomised, Thrive, Interventionist and Gradual, but not particularly extreme on any of these views.

Whilst this was my first thought, I don’t think it is likely to catch on. People generally prefer descriptive labels, and whilst the Myers-Briggs Type Indicators have their die-hard fans, this alphabet salad is unlikely to capture the imagination of many people.

My second thought was about animals. The two new axes already have animals associated with them – Fox and Hedgehog; Dove and Hawk. There are some fairly obvious associations for the original two axes as well. Dogs and Cats are fairly stereotypical exemplars of animals behaving in an Obliged and an Atomised manner respectively. Finally, the general attitude of “things will be fine” vs. “things will be terrible” that oversimplifies the Thrive and the Survive perspectives, are very much embodied by Wall Street’s Bulls and Bears cliché.

This probably isn’t very helpful either, but it does give us a great opportunity to get Dall-E to draw some anthropomorphised animals arguing about politics:

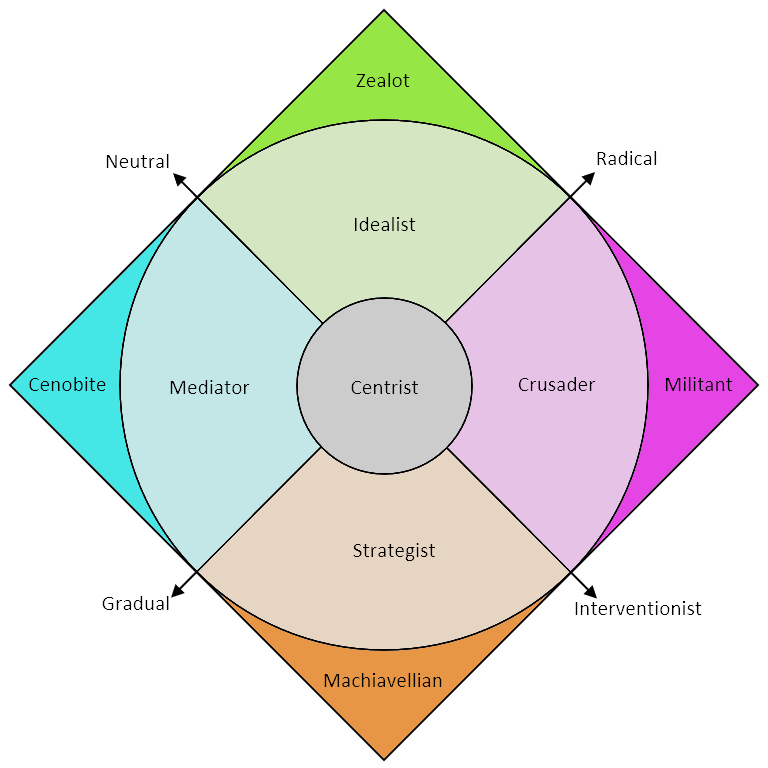

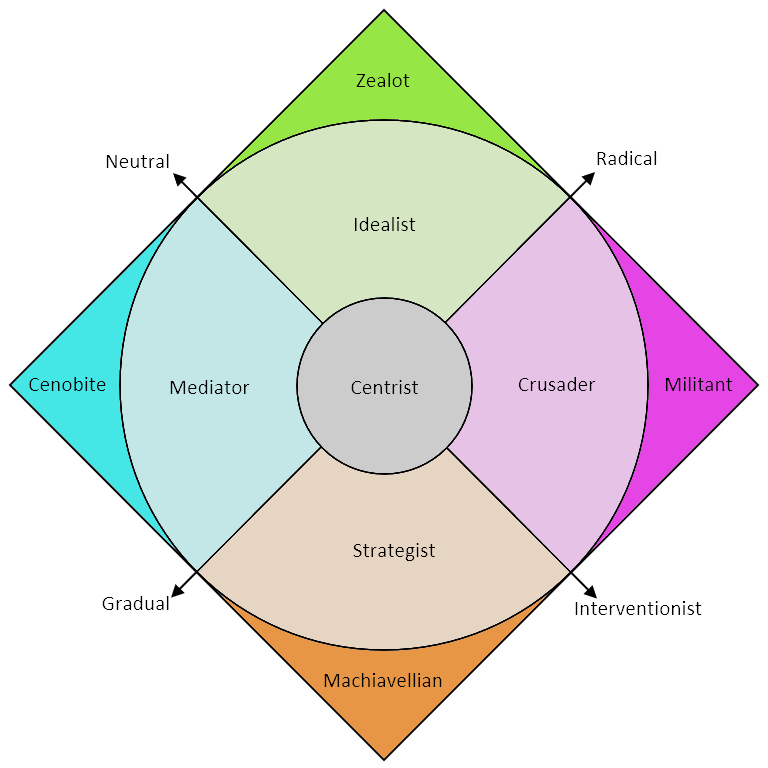

A Second Compass

I finally settled on a much simpler idea – a pair of political compasses (pun very much intended). We already have the first, which offers significant insight into modern political differences, and the meaning of “Left” and “Right”. What happens if we combine the two new axes into their own separate compass – what insight might that provide?

We can characterise the 4 different axes as follows:

| Individuals’ duties to one another: | Obliged – Atomised |

| The purpose of society for its people: | Thrive – Survive |

| Society’s role in the wider world: | Neutral – Interventionist |

| Approach to making changes: | Gradual – Radical |

Therefore the original political compass covers the axes expressing our views on “individuals’ duties to one another” and “the purpose of society for its people” – these could be summarised as “how you think the world should act on you”. The two new axes express our views on “society’s role in the wider world” and our preferred “approach to making changes” – in contrast to the first compass, these could be summarised as “how you think you should act on the world”. On this basis, I will now refer to these as the Inwards Compass and the Outwards Compass respectively.

This Outwards Compass gives us another four quadrants, and this time there is not an obvious way around to place the axes. I have chosen Gradual-Radical from bottom-left to top-right, and Neutral-Interventionist from top-left to bottom-right, because that is how it seemed to naturally align itself in my head. If you prefer it another way, don’t let me stop you.

The names I have picked for the four quadrants are hopefully reasonably descriptive:

| Gradual-Neutral | Mediator | Working with everyone without picking sides, avoiding any drastic action by pursuing compromise and encouraging restraint. |

| Gradual-Interventionist | Strategist | Pursuing long term goals by plotting a course, waiting for the right moments to act and avoiding overextension. |

| Radical-Neutral | Idealist | Trying to resolve problems as soon as they appear, without being distracted by what others are doing around them. |

| Radical-Interventionist | Crusader | Getting the job done as quickly as effectively as possible, bypassing or removing roadblocks wherever necessary. |

I asked Dall-E for some more D&D characters that were representative of these labels, and these were my favourites:

Outwards Extremes

As with the original political compass, these are all potentially perfectly reasonable approaches, but any one of them could be problematic if taken to extremes. The issues with extreme Interventionism and Radicalism are fairly obvious, but it is also harmful if Neutrality turns into isolationism, or if a preference for gradual change turns into a resistance to any change at all.

Whilst many people are quite happy to be considered Interventionists or Radicals, I chose to name the other ends of these axes Neutral and Gradual, because the extremes of Isolationist and Stagnant are pretty negative. It is important that the labels of the axes themselves resonate with people, as otherwise they do a poor job of expressing the range of opinion in the population. If the axes are labelled in an unappealing way, everyone will simply consider themselves to be a centrist.

If we are specifically discussing labels for the extremes though, we don’t have to worry about their mass appeal. With that in mind, I offer the following labels:

Cenobite as the extreme of Gradual and Neutral – cenobitic communities were both isolationist and unchanging. An example of this might be Japan’s Edo period, which is renowned for its commitment to isolationism, and its resistance to change.

Machiavellian as the extreme of Gradual and Interventionist – Machiavellian is used to describe plotting, duplicity and the pursuit of power above all else. The British Empire should definitely be a contender for this, playing opponents off against each other over centuries, and manipulating entire continents for its own gain, without regard for the cost to anyone but itself.

Zealot as the extreme of Radical and Neutral – zealots are uncompromising in their pursuit of their ideals, but are often unconcerned about those outside their sphere of influence. During its Cultural Revolution, China was isolationist, but also engulfed in internal turmoil as its government sought to make radical societal changes whilst enforcing strict ideological purity.

Militant as the extreme of Radical and Interventionist – militants are also uncompromising, but their focus is often on bringing the world into line with their ideology. Cuban Revolutionaries, supporting guerilla warfare across South America fit this category – offering their help to any that were willing to take up cause against the US and global capitalist interests.

This gives me an “outwards compass” that looks like this:

Alternative Compasses

Feel free to skip this section if you aren’t interested in alternative formulations.

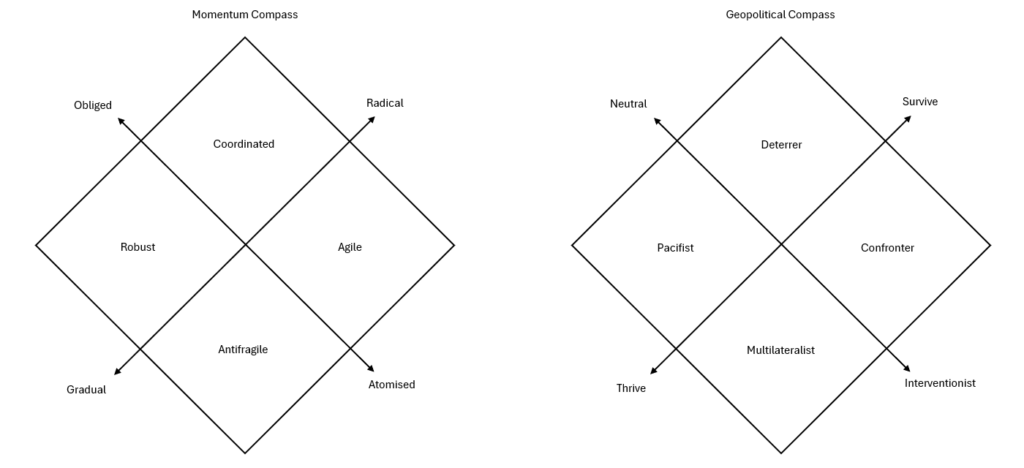

The axes don’t necessarily have to be paired together in this way. Personally, I quite like this approach, as the inwards compass is very recognisable and clearly shows the left-right divide, whilst the labels for the outwards compass feel very natural and informative. Given my earlier mention of geopolitics however, I feel that briefly exploring alternatives is worthwhile.

We could instead pair “Thrive – Survive” with “Neutral – Interventionist” to form one compass, and “Obliged – Atomised” with “Gradual – Radical” to form the other. This first compass then covers society’s purpose for its people and role in the wider world, and I have already described its quadrants above:

| Neutral-Thrive | Costa Rica | Pacifist |

| Neutral-Survive | Switzerland | Deterrer |

| Interventionist-Thrive | NATO | Multilateralist |

| Interventionist-Survive | Russia | Confronter |

The second compass could then be considered to cover something like the “size” and “speed” of a society. A very obliged society is one in which decisions necessarily affect a large number of people, and is therefore in some sense “large”. Similarly a radical society makes changes quickly and is therefore “fast”. In Nassim Taleb’s book Antifragile, he discusses at length the idea that things being large and fast makes them fragile, and that systems that allow for gradual change across many smaller entities may achieve what he terms “antifragility”, where they are not just robust against shocks, but actually gain from disorder. This allows me to use (abuse?) this concept and terminology for this compass:

| Obliged-Radical | Large & Fast | |

| Obliged-Gradual | Large & Slow | Robust |

| Atomised-Radical | Small & Fast | Agile |

| Atomised-Gradual | Small & Slow | Antifragile |

I am inclined to call these two compasses the “Geopolitical Compass” and the “Momentum Compass”, and I think they do offer additional insight. Whilst I might not agree with the positions, I can at least understand the appeal of all of the quadrants on the inwards and outwards compasses, such as Nationalism or Idealism. This arrangement of axes however yields one quadrant that I just cannot fathom.

It is hard to see the label “Fragile” as anything but negative, so in line with my previous points I have changed it to “Coordinated”, because a society would have to be very well coordinated to be able to withstand rapid changes whilst being so interconnected. Perhaps it is my bias showing, but I think fragile is a better fit. An obliged society has a myriad of dependencies both visible and invisible, by the very nature of people being obliged to each other, making it a complex system. Most attempts to make rapid changes to a complex system are going to be a disaster, because there will inevitably be interactions that haven’t been considered.

The “Coordinated” quadrant is the one in which Socialist and Nationalist revolutionaries reside, and I have always had a problem with the “everything is terrible, let’s burn civilisation to the ground so a new, better society can rise from the ashes” point of view. In contrast, Liberal or Corporatist revolutionaries aren’t really a thing, simply by their atomised nature – the entities that someone in the “Agile” quadrant might try to revolutionise are generally smaller than literally the entirety of civilisation, so when things go wrong, it has less scope to be catastrophic.

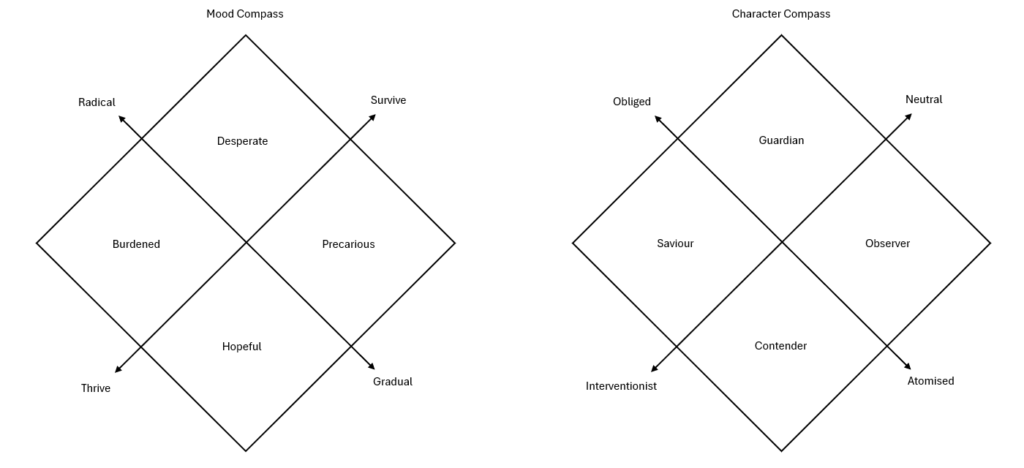

The third possible pairing of axes is “Thrive – Survive” with “Gradual – Radical” for one compass, and “Neutral – Interventionist” with “Obliged – Atomised” for the other. To me, the addition of “Gradual – Radical” to the concepts of Thrive and Survive, makes each quadrant feel like a mood or vibe.

Survive, as ever, evokes the idea that “civilization is hanging by a thread”, but combined with Gradual, suggests a kind of knife-edge, tightrope walk situation where things are precarious, so you mustn’t make any sudden moves. In contrast, Radical suggests a kind of desperation – no small measures will save us, it’s our last chance so go big or go home!

Thrive combined with Gradual seems fairly straightforward – a kind of cautious optimism, that I’d describe as hopeful. Things are pretty good, so let’s keep improving them carefully. It is its combination with Radical that I found more tricky to describe. After all, the drive to do things quickly is unlikely to be due to desperation, as this goes against the fundamental basis of a Thrive mindset. Instead, the need for speed is more likely to be driven by the presence of a burden – either the realisation that you only have one lifetime to accomplish everything you have set out to do, or the guilt of living in comfort while others are not as lucky, driving a desire for rapid changes to address the disparity.

| Thrive-Radical | “Moral Culpability” | Burdened |

| Thrive-Gradual | “Cautious Optimism” | Hopeful |

| Survive-Radical | “Do-or-die” | Desperate |

| Survive-Gradual | “Knife-edge” | Precarious |

These labels are definitely less appealing than those of the previous compasses, but it is important to note that they are descriptions of how we view society, and not descriptions of people themselves.

This leaves the final pair of axes to analyse. I found myself visualising these almost like characters or personalities. The Obliged ones are motivated to act on behalf of others – either in an inwards looking way, to guard their society, or in an outwards looking way, to march out and save their society from external threats.

The Atomised ones in contrast, can probably take actions more freely, choosing how and when to get involved. The Neutral quadrant preferring to observe, avoiding entanglements, and the Interventionist quadrant being more inclined to get stuck in and “play the game”.

| Interventionist-Obliged | “The greater good” | Saviour |

| Interventionist-Atomised | “Play the game” | Contender |

| Neutral-Obliged | “Cultivate your garden” | Guardian |

| Neutral-Atomised | “Keep to yourself” | Observer |

On this basis, I shall call these two compasses the “Mood Compass” and the “Character Compass”. My first impression is that this framing is less useful than the other two – at the very least, I didn’t get any flashes of inspiration or understanding from it. I also like these labels the least – they sound a bit contrived, and I’m definitely overloading the words, trying to encapsulate a lot of nuanced meaning within the two-word phrases. Nevertheless, I have included it here both for completeness, and because it may be useful to other people who have a different perspective.

This gives us three ways to label each of the sixteen possible positions:

| Axis Positions | Inwards & Outwards | Momentum & Geopolitical | Mood & Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATIG | Liberal Strategist | Antifragile Multilateralist | Hopeful Contender |

| ATIR | Liberal Crusader | Agile Multilateralist | Burdened Contender |

| ATNR | Liberal Idealist | Agile Pacifist | Burdened Observer |

| ATNG | Liberal Mediator | Antifragile Pacifist | Hopeful Observer |

| ASIG | Corporatist Strategist | Antifragile Confronter | Precarious Contender |

| ASIR | Corporatist Crusader | Agile Confronter | Desperate Contender |

| ASNR | Corporatist Idealist | Agile Deterrer | Desperate Observer |

| ASNG | Corporatist Mediator | Antifragile Deterrer | Precarious Observer |

| OSIG | Nationalist Strategist | Robust Confronter | Precarious Saviour |

| OSIR | Nationalist Crusader | Coordinated Confronter | Desperate Saviour |

| OSNR | Nationalist Idealist | Coordinated Deterrer | Desperate Guardian |

| OSNG | Nationalist Mediator | Robust Deterrer | Precarious Guardian |

| OTIG | Socialist Strategist | Robust Multilateralist | Hopeful Saviour |

| OTIR | Socialist Crusader | Coordinated Multilateralist | Burdened Saviour |

| OTNR | Socialist Idealist | Coordinated Pacifist | Burdened Guardian |

| OTNG | Socialist Mediator | Robust Pacifist | Hopeful Guardian |

The “Inwards & Outwards” column definitely seems the most useful and relatable to me, so I am happy to leave further exploration of the alternatives as an exercise for anyone that finds them particularly informative or inspiring.

Conclusion

The combination of the inwards and outwards compasses covers all 4 dimensions that have been discussed, and hopefully provide a relatively concise and relatable description for a huge range of political views. I consider myself to be a Liberal Strategist, and am very comfortable with that label, but I also know people that I consider to be Socialist Crusaders, Liberal Idealists, and Corporatist Mediators, who I think would be very happy with those descriptions too. I will admit to not personally knowing any self-described Nationalists, though I think this is due to the fact that I am Liberal and that the inferential distance between Liberal and Nationalist makes it difficult to form such connections. From what I can tell though, the label of Nationalist does appear to be slowly losing some of its stigma, so this may not be an entirely unwelcome description either.

Given that the previous attempts at breaking politics out from a single dimension have had very limited success, I don’t expect this to be anything more than a niche interest. I do hope though, that it provides some people with either interesting insight, a useful mental model, or a jumping off point for research or introspection. I would love to know what anyone that has read this post considers themselves to be, so if you got this far, please consider leaving a comment!

2 Replies to “The Political Compass – More than Just a Meme”